Written by Nick Curtis, Evening Standard, 1 September 2011

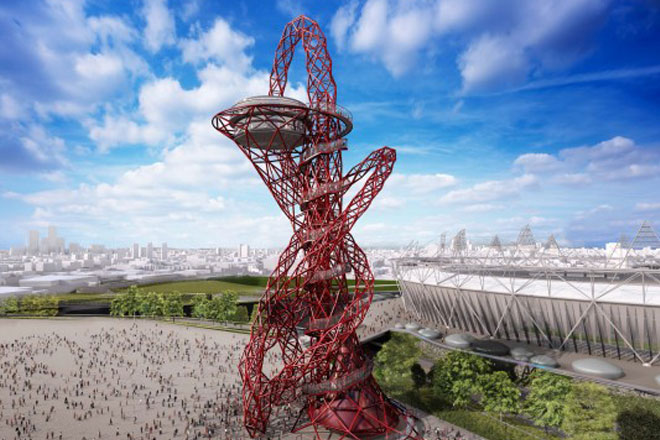

“People call it a roller-coaster, a hookah pipe, a sculpture, a building or just a big red thing. And they either love it or hate it.” So says one of the builders of the ArcelorMittal Orbit, the elliptically looping observation tower designed by sculptor Anish Kapoor and architect-engineer-designer Cecil Balmond, and largely gifted to the London 2012 Olympic Park by Britain’s richest man, steel tycoon Lakshmi Mittal.

Seen close up, at 76 metres of its eventual 114.5m height, the Orbit also recalls an anatomical model, its central tower and unfinished loops splaying open like severed arteries. The 50-tonne cradle of one of the two vast viewing platforms – the heaviest section to be lifted into place so far – recalls the trepanned base of a giant skull. The whole thing, its parts and its incomplete whole, is huge and very impressive.

The Orbit has been a much-discussed element of the Olympic Park. It grew out of the decision in 2008 by Boris Johnson and the then Olympics Minister Tessa Jowell that the Hackney Wick site needed “something extra” akin to the Eiffel Tower to “arouse the curiosity and wonder of Londoners and visitors”.

Mittal reportedly came on board after a chance conversation with Johnson lasting “about 45 seconds” at Davos in 2009, and at first he agreed to supply the steel. Once Kapoor and Balmond’s design was chosen – reportedly over those of Antony Gormley and others – the tycoon became intrinsically involved in the project. He is funding £19.6 million of the £22.7 million cost with the outstanding £3.1 million coming from the Greater London Authority.

There will be 1,500 tonnes of steel in the structure, all of it from Mittal factories, and 63 per cent of it recycled. “The ArcelorMittal Orbit is my contribution to the country that I’ve come to think of as home,” Mittal explains. “It is my way of giving something back to the people and business community who have supported me here. It’s a great pleasure to be able to provide such an iconic element of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, which” – he adds with a canny smile – “will also be a tribute to the versatility of steel as a material for the modern world.”

Visitors to the Orbit, when it opens next May, will enter via the base, which will be canopied to keep lighting levels low, and will rise up the tower in two 21-person lifts, also dimly lit. They will step out onto one of two enclosed 300sq m viewing platforms overlooking the Olympic Park and a further 250 acres of the capital. Descent will be via a spiral staircase that wraps around the tower, through which sunlight will filter. Mittal’s people believe the Orbit can accommodate between 500 and 750 people an hour, or 5,000 a day, or a million in its first year. This is an Olympic project already anticipating a popular life beyond the Olympics.

Kapoor described the chance to build the tower, Britain’s largest piece of public art, as “the commission of a lifetime” and said he wanted a design with “something mythic about it”. Balmond envisaged something “never centred, never quite vertical”, and both pictured a fusing of radical art and engineering for something that uses apparent “instabilities as stabilities”.

Admirers noted the design’s radicalism, elegance and its subtle evocation of the Olympic rings. Elsewhere, the usual media suspects ganged up to slag off the tower as a waste, a white elephant or a monument to Johnson’s ego. But this was before the Orbit started to go up. And it has gone up at a surprising rate.

Since the foundations were sunk in February – 49 concrete piles, each 25 metres deep – the Orbit has risen by four metres a week. At first, each of the 366, five-tonne “star junctions” was bolted individually into place: as the tower got higher, they were assembled into rings on the ground and lifted into place. The erectors are lifted onto the structure by crane, their compressed air torque guns tied to them. Once drilled home, the 35,000 bolts are painted to match the blood-sausage colour of the steel tubes, which is called, prosaically, RAL 3003. The first maintenance on the project – touching up the original 19,000 litres of paint – is scheduled for 20 years’ time. Once complete, the Orbit should stand up “for ever”.

The lower viewing platform is due to be hoisted into place later this month, followed by the remainder of the main structure. Then comes the fit-out in the winter months. The plant room controlling the lifts and air conditioning will be plonked on the roof of the upper viewing platform, and a tuned mass damper – basically a 58-tonne steel pendulum to compensate for the tower’s movement in wind – will be installed. Mittal himself is impressed by the speed of construction. “I’m confident visitors will marvel at Anish Kapoor’s vision and Cecil Balmond’s ingenuity when it is complete.”

Apart from crane drivers and painters and fitters-out, the actual, physical assembling of the Orbit has been down to a team of four erectors, under the guidance of “dimensional engineer and token Aussie” Wayne Heaton and construction manager John Calland. Both men are slightly blasé veterans of big construction projects both on the Olympic site (they built the Velodrome, Stadium and Aquatic Centre) and elsewhere (they’ve worked on Heathrow’s Terminal 5 and the Shard of Glass). But even they admit the Orbit is complicated.

Most buildings are plum and square – the Orbit is neither. Some of its curves are structural, some are aesthetic, and all of them are subject to difficult stresses until they are completed and the whole thing is in balance.

Heaton and Calland monitor the structure on laptops running the 3D program that Kapoor and Balmond used to design the Orbit, which plots the entire history of every component. Each lift is carefully planned. “You don’t want to get a 50-tonne piece of steel up high and find it’s the wrong way round,” says Heaton. “Wind is our main enemy,” adds Calland. “They stop us working at height on cranes at quite low speeds, especially since we’ve risen above the wind shadow of the stadium.”

But do you like the Orbit, I ask? “When it’s finished, that will be the time to make a judgment,” says Heaton, “but I think it’s indicative of London, a complicated structure for a complicated city.”

“When we put a big piece up and it changes the skyline, you do stand back for a bit and look at it,” says Calland. “The Orbit contrasts with the white starkness of the other Olympic buildings and I’m sure it will be an asset after the Games. It’s going to be a focus point.”